Gathering evidence and learning through an alternative process of testing with pilots, randomized control trials (RCTs) that help illustrate what works to improve urban refugee livelihoods.

|

|

|

There is limited research about what livelihoods services work for urban refugees, and how to improve social cohesion in the cities that refugees and hosts share. Our research aims to build evidence in four (4) areas that have promising, but limited evidence:

- Whether certain interventions are more or less effective for refugees.

- The impact of different delivery models.

- The impact of building social networks for refugees.

- The impact of livelihoods programs on social cohesion.

What we learn is shared widely and used to adjust the services as we deliver.

Randomized Control Trials (RCTs)

A key foundation of Re:BUiLD’s Evidence and Learning strategy is rigorous impact evaluations that seek to establish the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of specific interventions and delivery approaches to address the barriers urban refugees experience as they pursue economic self-reliance. Re:BUiLD has undertaken two waves of impact level research with three specific RCTs, one in Nairobi, one in Kampala and one in both Kampala and Nairobi.

The RCTs seek to find:

- The most cost-effective package for micro-enterprise services to improve self-employment outcomes for urban refugees and vulnerable host community members.

- The cost- effective ways to promote interpersonal contact between urban refugees and host community members to reduce discrimination, build trust, social cohesion and improve economic outcomes.

Wave 1 RCT

The studies are registered with the American Economic Association's (AEA) registry for Randomized Controlled Trials. They can be accessed here:

Re:BUiLD concluded the implementation of the two large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in Kampala, Uganda and Nairobi, Kenya. Both looked at one common dimension of livelihood programs supporting microentrepreneurs: mentorship services where the mentors were microentrepreneurs themselves. Administered from the IRC’s Livelihood Centers in each capital, the studies have the potential to inform IRC’s programming around the world as well as other many policy organizations looking to improve microentrepreneurs' livelihoods in urban settings.

Study Design

The studies targeted microentrepreneurs who would be eligible for IRC’s typical microenterprise programming.

Both studies had four major treatment arms:

- Control, which was in fact a delayed treatment group.

- Cash Only, which consisted only of a business grant.

- Basic Mentorship, which included a business grant plus a traditional mentorship program.

- Mentorship « Plus », which was designed differently in each study, and in both cases aimed at answering a more specific set of hypotheses around how exactly the mentorship works, and looked into what features of mentorship could make it more or less likely to succeed.

Additionally, both studies also had a subsequent randomization which made the demographic match between mentors and mentees vary on nationality and gender dimensions. This allowed for the study of the effect of exposure to diverse peers on social cohesion, attitudes, and perceptions, but also on network building and economic success.

In Uganda, each mentor was assigned to three mentees, with whom they formed a mentorship group, which could be either homogeneous (everybody has the same gender, same nationality), mixed gender (everybody has the same nationality, genders vary) or mixed nationality (everybody has the same gender, nationalities vary). In Kenya, a mentor was assigned to one mentee; and while all mentors were Kenyans, they were randomly assigned to a fellow Kenyan (same nationality) mentee or to a refugee (other nationality) mentee.

Research Questions

Both studies looked at the same broad set of research questions:

- Does mentorship help the economic success of microentrepreneurs? And if yes, what features of mentorship could drive this relationship?

- Does exposure to individuals from different groups and nationalities improve social cohesion and can it change attitudes towards others?

Common sets of outcomes

While the exact formulation of survey questions differed slightly to match the context of the country and the study in question, the data collected allowed for the construction of parallel pictures on the economic, psychological and sociological situation of vulnerable youths in both cities.

The studies also shared some primary outcomes defined and measured in the exact same way. This included:

- Having a business open

- Self-reported business profits

- Household well-being

- Psychological well-being

- Social cohesion, such as interactions with refugees and hosts

- Attitudes towards refugee policies

Key Findings

Uganda

- Cash grants had significant, positive impacts on business performance, household well-being, and social cohesion over a 12-month period.

- Participation in a mentorship program did not significantly alter business outcomes on average. These results included slightly positive effects for men and slightly negative effects for women, with the adverse impacts of mentorship being more pronounced among those paired with female mentors.

- Mentorship was not correlated with the expansion of business networks or with enhanced social cohesion or policy perspectives beyond the positive effects observed from cash grants alone.

The published working paper can be accessed here.

The key findings from Wave 1 of the Randomized Control Trial (RCT) implemented in Uganda can be accessed in the policy brief here.

Kenya

- The findings indicate that the combination of cash and mentorship significantly increased the probability of business ownership in both the short- and medium term. Additionally, there were sustained improvements in various indicators of business success among the participants.

- The program effectively supported subsistence businesses and helped existing business owners maintain their enterprises, although significant profits are only seen after nine months.

- Cash and mentorship programs were ineffective in improving business outcomes for refugee women due to high initial business ownership and systemic barriers.

- Mentorship combined with cash transfer led to significant profit increases and improved psychological well-being for Kenyan men, with success linked to the mentor’s network size.

- Cash only is more cost-effective in achieving economic results compared to cash + mentorship, but it does not account for social cohesion or psychological effects.

The key findings from Wave 1 of the Randomized Control Trial (RCT) implemented in Kenya can be accessed in the policy brief here.

Wave 2 RCT

The study is registered with the American Economic Association's (AEA) registry for Randomized Controlled Trials. It can be accessed here.

The RCT Wave 2 tests the impact of business grants and activities that build business and social networks on business success and social cohesion.

Why networks?

- Remove information constraints (on market gaps, business locations, suppliers/customers/lenders, administrative burdens, broader learning, etc.)

- Facilitate cooperation and collaboration, including:

- Resource-sharing (stalls, supplies, capital inputs)

- Risk-pooling (e.g., savings and credit)

- Provide word-of-mouth marketing

- Increase social solidarity, etc.

- Improve psychological wellbeing

What do we want to learn from the Wave 2 RCT?

- How can we support the development of business networks and social capital of urban refugees and hosts?

- Are these interventions effective (and cost-effective) at improving economic self-reliance, self-employment, and social cohesion between refugees and hosts?

- What kinds of networks are more or less impactful?

- For whom are these interventions most impactful?

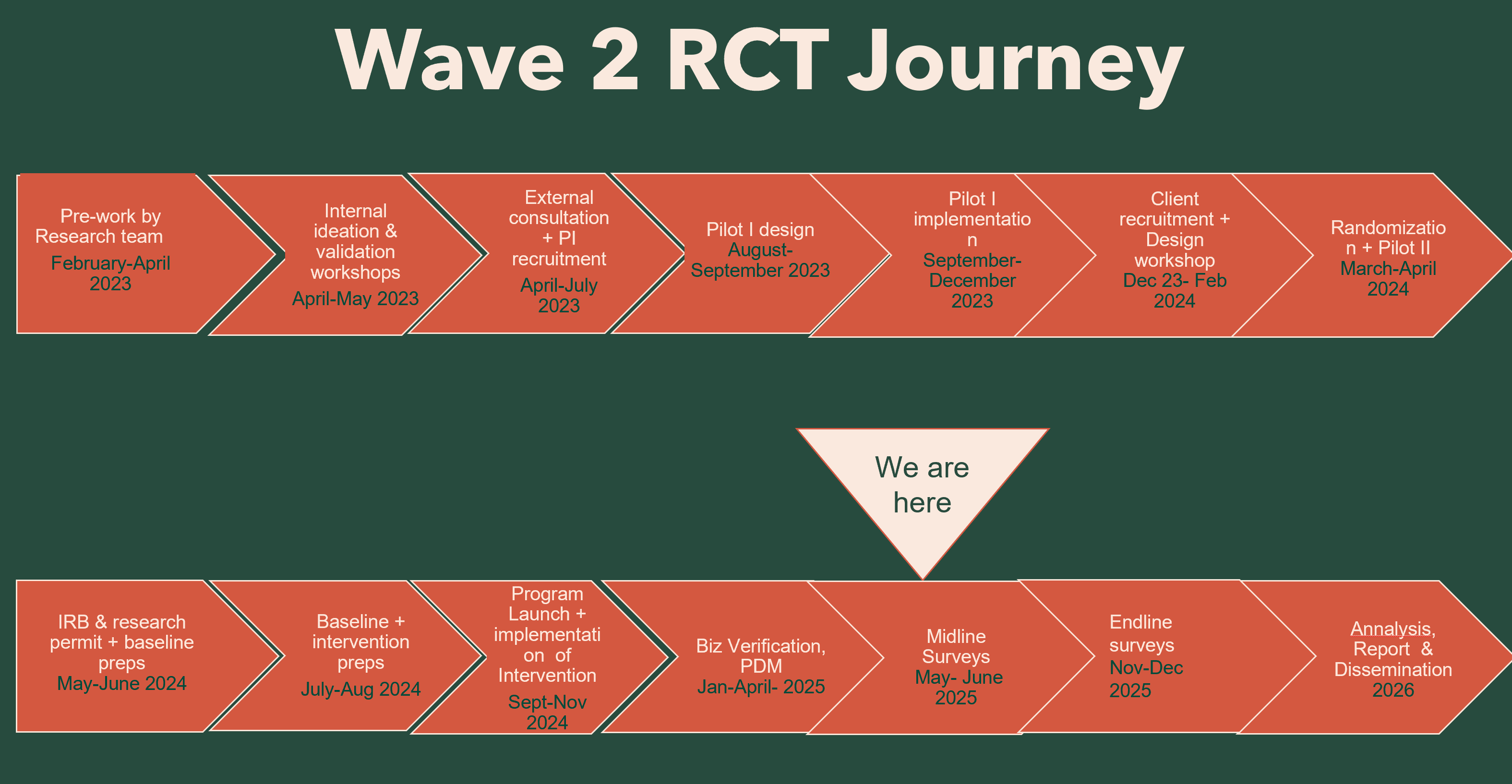

Progress to date

Research Partners

Re:BUiLD work research partners support in designing and implementation of the studies, and lead the analysis. The research partners Georgetown University (GU), Center for Global Development (CGD), Innovation for Poverty Action’s Displaced Livelihoods Initiative, Rochester University (RU), Princeton University (PU), Makerere University, Stanford University (Immigration Policy Lab) and the Economic Policy Research Center (EPRC).